He bounds in every morning, obsessed with the night before. The winners. The losers. Who moved into first place. Who moved into last.

What follows is a 6-year-old’s version of “SportsCenter.”

“Hey Doddy, guess wot? Hey Doddy, guess wot?” Within minutes he’s ripped through everything from how Steph Curry and the Warriors are doing to who’s up to fourth in the NHL’s Central Division. (Important note: his sportswriter father might not be able name all the teams in the Central Division, let alone know who is what place at any given moment).

He is, in just about every way, a 4-foot version of myself. Will Graves 2.0. Precocious. Energetic. A bit obnoxious (which you can get away with when you’re in first grade, not so much when you’re 41). A little sweeter than his old man (his mother’s influence thank God) but with a bite that will sometimes surprise you. (Note to any 6-year-old’s reading this, the phrase “Mommy Days stink” should never exit your lips, trust me).

He is, even more so than I was at his age, obsessed with sports. We didn’t push it on him. It just sort of happened. He figured out pretty early daddy went to the games and talked to the players. But as the preoccupations of his young childhood faded (see you later “Thomas & Friends,” don’t miss you a lick weird, bald-headed “Caillou,” are we really past the “Cars” phase already? Sigh.) a new one emerged.

Baseball. Football. Basketball. Hockey. Soccer (true story: he dropped an MLS reference on a buddy a couple of weeks ago). He loves analyzing the stats of his favorite players (and some random ones too). I’ve written a series of very basic children’s sports books and occasionally I’ll find him laying on his bed flipping from one page to the next. “Hey Doddy, guess who was a good team? The 2013 Miami Heat. Hey Doddy, guess who won Super Bowl X-V-I-I?” He knows the answers, packing them somewhere in his brain between what he wants for dinner (usually tacos) and whether or not he has gym that day (translation: Doddy will let him wear sweat pants if he does).

It is fascinating to watch him jump around while watching NBA highlights, for him to constantly provide updates that happen to scroll across the bottom, to reflexively flip to one of the ESPNs in search of a game, ANY game (we’ve watched softball and cricket and Monster Truck racing together).

He is a fan. And there is a purity in his fandom that provides with me a daily reminder on why I love my job, absurd as it occasionally may be. He doesn’t care about salaries or free agency. He’s never known a Pittsburgh Pirates team with a losing record or the Pittsburgh Steelers as Super Bowl champions. His shirt drawer is filled with hoodies and T-shirts of his favorite teams and his favorite players. Guys I know. Guys I cover. Guys I like. Guys I don’t. Guys who don’t like me.

I often think about how much of my job to share with him. Then I think back to what I knew about the men I idolized when I was his age, lower-case gods who didn’t have to deal with the 24/7 news cycle or social media, developments that kept my opinion of them restricted largely to how they did on the field. It wasn’t colored by their Twitter feeds or their Facebook posts or some Vine that got sent to Deadspin or TMZ, things I am thankful for. Things I will try to shield him from, though reality is only one revelation from a blabbermouth 4th-grader on the bus away.

His interest has less to do with the players winning — though he has already become uncomfortably obsessed with results (example: when we turn on some random game, he automatically starts backing whichever team happens to be up) — than the actual GAMES they are playing. Games he can play. With his friends. With his father. With himself.

His joy is evident. His smile unmissable. The way he cocks back his right arm to throw a pretty damn good spiral for a kid his age. The intent look on his face every time he grabs a bat and eyes the ball on the tee. The sound of his voice doing play-by-play during the imaginary showdowns in his head, the ones that make me feel 12 again, when I threw myself onto the ground in our backyard to score the clinching touchdown (to the puzzlement of my parents and the neighbors) or pulled up to hit the winning jumper at the buzzer over and over and over again.

Yet back then I never worried about the risks. You played with your buddies and you got knocked around. I have no doubt my first concussion came when I was maybe 8-9 and playing in the street, my head bouncing off the asphalt when another kid tried to two-hand touch me into oblivion. I remember seeing stars, breaking down in tears and riding my bike home in a daze. The next one almost certainly came during my one year playing organized football, when _ as a 58-pound left tackle in a 75-pound league _ I was bowled over on a running play and woke up looking at the moon. There was the time in high school when I was clotheslined (I can still see Chris W in midair, his right arm extended). I laid on the ground for several seconds (no tears, thankfully) and kept playing. Then there was the street hockey game where the ball popped up in front of my face and the opponent in front of me grabbed his stick like a bat, swung and missed the ball … but not the front of my goalie cage.

I never went to the doctor. I never told my parents. I didn’t even really think about it once the headaches went away. It was part of the game.

I’ve heard that phrase over and over again in my professional life from athletes (not just football players) coming back from injury, concussions or otherwise. It’s a cliche I try to keep out of my copy, but one I have some sense of fealty to because, hell, I always figured it was.

But it’s one thing when it’s your head, your health, your pain. It’s another when it’s your child’s. I am not a helicopter parent (the morning routine in our house after my wife leaves every morning could best be described as polite anarchy) but I ask our kids “Are you OK?” so much it comes off as a nervous tic (and maybe it is).

Our son’s second Little League season awaits. He has more than a token interest in basketball (our Nerf games in his room are suitably epic) and his affinity for football (at least throwing it and catching it) is growing by the day. My wife and I have talked about what to do when he asks to play Big Boy Tackle Football.

Thankfully for now we don’t have to worry about giving him a serious answer. For now, simple games of catch _ the ones that end with a “Gronk Spike” _ are enough. Maybe by the time he’s big enough (at 48 pounds he’s still more Pop Tart material than Pop Warner material) the medical community will have some sort of consensus on how to deal with head injuries.

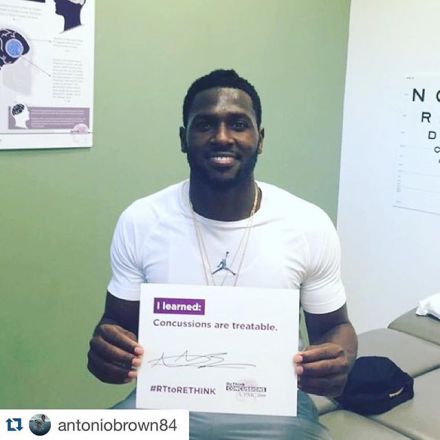

The science is evolving, but hardly fast enough to provide anything resembling consenus. Some doctors feel concussions are complex but treatable and apparently some of the guys they take care of agree:

Treatable, maybe, but treatable is far different than avoidable.

And that’s the part where the journalist in me and the dad in me can’t seem to agree on well, a lot of things.

The NFL acknowledged there was a 58 percent increase in reported concussions this season even as the league has tried to take steps to eradicate the kind of play that leads to them in the first place.

You know, plays like this (which Deadspin perfectly described as an “assassination attempt“) against Pittsburgh wide receiver Antonio Brown (and the reason the two-time All-Pro is in the above picture in the first place) in playoffs a few weeks ago:

The league ended up suspending Burfict for the first three games of next season, not so much for this one individual shot as much as his rapidly growing resume of hyper-aggressive plays make it appear he’s playing “whack a mole” with someone else’s life.

These hits _ for decades legal (google: Jack Tatum, Sammy White and Super Bowl XI if you need proof) _ are now either “a part of the game” or “criminal” depending on which side of the Ohio/Pennsylvania border you happen to live on. An hour before Burfict drilled Brown, Steelers linebacker Ryan Shazier was neither fined or flagged for this:

The sportswriter #HotTake (note: I am decidedly anti-hot take) is that there is a war on football. Not exactly. Ray Rice knocked his fiance out, and people still watched. The drumbeat of former players concerned about the long-term health effects of treating their bodies (and particularly their heads) like well-muscled but hardly invincible pinballs for years is growing louder. And still 62.9 million people clicked to the final minutes of the AFC Championship game.

There is no war, at least not one you can see at the professional level. The ratings have rarely been better. The money never more astronomical. The stardom of the league’s bold-faced names never more widespread.

The real battle, the one whose ripple effects won’t be felt maybe for decades, is happening at dinner tables across the U.S. between parents of their own little 6-year-old Antonio Brown wannabes, the ones who watch the games on TV, follow their heroes on Twitter, hear the roars, see the commercials and the highlights and dream of pulling a jersey over their own heads one day, running out of the tunnel and “Dabbing” to his heart’s content.

For now I can keep my son satisfied with a Nerf ball and our own imaginary 2-minute drills, the one where we have to go from our mailbox to the neighbor’s before the clock hits zero to win the game.

Yet those days are dwindling. He’s going to start asking more frequently, more seriously, if he can put on pads and play for real.

And I will try to reconcile the writer who makes a living chronicling a league and a sport celebrated in no small part for its brutality with the parent who isn’t sure he wants to send his small but rapidly growing firstborn into harm’s way.

The writer in me believes the dangers of football (or any contact sport) are self-evident, just like smoking. Watch a game for 10 minutes and you know what you’re getting into. Firefighters will go to every elementary school in the country this year, hand out plastic red helmets and teach kids to “Stop, Drop and Roll” to avoid smoke in case of fire. How anyone thought inhaling a slightly filtered version of that same smoke into their lungs intentionally was a good idea, I’ll never understand.

While I sympathize with players and families dealing with CTE, I can’t ever remember a time when one NFL player _ or any player for that matter _ say he was forced to play against his will.

I freely admit that viewpoint is cynical with hints of hypocrisy and hindsight elitism. And yet I can’t shake it. And I understand that there’s no guarantee he’ll suffer any sort of long-term effects from playing football as opposed to anything else.

Still, I can’t help but wonder if his dreams are allowed to come at the expense of my wife and I’s unspoken terror.

A coach I once covered likened every play to a car accident. When I asked him why he felt it necessary to have one running back carry the ball on 19 straight plays (or “19 straight car accidents” as I called it) he flushed and said he was simply trying to get the game over as quickly as possible.

Look, there’s a Senior Golf Tour. Gyms across the country are filled with guys playing basketball into their 60s and beyond. The same goes for tennis and soccer (and even hockey) and on and on and on.

Not in football, which is typically relegated to once a year Turkey Bowls. Why? Because it hurts like hell. Because it’s dangerous. Because the risks of what can happen when the ball is snapped are clear and hardly worth the pain when there aren’t millions of dollars on the line.

Yet my son doesn’t know that. He just wants to watch the game. He wants to know the score. He wants to pretend to be the guys his father spends so much time writing about. He wants to join them on the field.

And each day that goes by brings us closer to the day when his mother and I will have to give him a real answer.

Right now, we have no idea what it’s going to be. And we’re not the only ones.