This was supposed to start with a hero shot.

I had it all planned. Me sitting in one of those beige chairs inside the cancer treatment center that at times over the last seven years has become a second home. IV needle jabbed into a vein on my left hand. The rack holding my meds placed ever so conveniently over my left shoulder in the background, probably with the big bag of obinutuzumab hanging from it. A look of calculated hopeful weariness on my face.

Maybe, I thought, I’ll wait until the rash that typically accompanies my infusion starts. Or maybe I’ll take video of the shakes I get. All of it carefully designed to elicit some combination of sympathy, empathy and inspiration.

My mother and sister laugh when I tell them this. They think I’m kidding. My wife knows better. She knows I’m not.

I joked when I was initially diagnosed with Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia in March, 2014 that I was lucky. That I had some form of incurable cancer that was somehow, too much of a slacker to kill me. What a break. I mean, there are few things more powerful than to end any conversation with “who cares, I have cancer.”

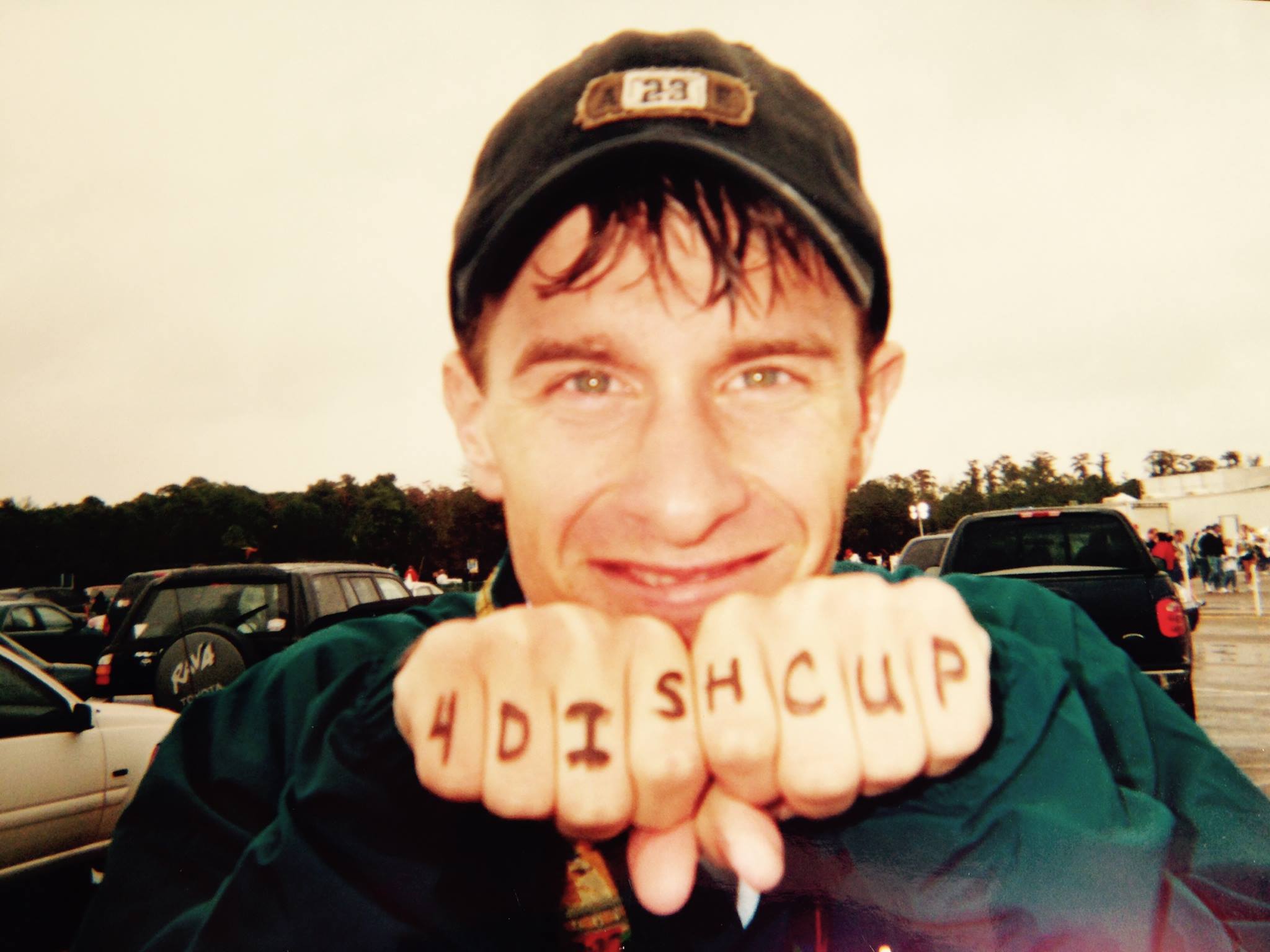

Now it’s become a punchline, an excuse I use to try to get out of everything from doing the dishes to cleaning the litter box to (insert unwanted daily chore here). (Note: I get out of none of those things).

It’s back now for a third time. My blood numbers — the ones I have become a relative expert in — told me last fall this was coming. Even though I look fine. Even though most days I feel fine. Even though by every metric outside of numbers on a page, I am as healthy as the next dad-bodded 40-something slightly overweight because I mean, who doesn’t love cookies, sports writer.

And while there was a sense of dread as I watched the cancer steadily peck away at my red blood cells, in a way there was also this mix of “OK, cool, cancer is back baby! Hero time!”

This sounds dumb. Hell, it is dumb. But in a way, I look back at the spring of 2014 — when I really was sick — with nostalgia. For a while, everything else fell away. I semi-coasted at work (even more than usual). I vividly remember getting into the idea of making dinner for my wife and the kids, often the highlight of my day. Nothing else mattered. Who was getting hired. Who was getting fired. Which of my colleagues were getting the assignments (I wasn’t getting). My seemingly endless pursuit for professional relevance in the city that has become my adopted home.

My days became a series of never-ending internal diagnostic tests, both physically and spiritually. How hard was my heart working as I climbed the steps. What the latest blood panel looked like. Then, as the meds started work, how was I going to use this reprieve to recalibrate everything.

I thought it’d be automatic. That somehow God would be like, “OK kid, I gave you this thing that’s manageable but I want you to make some changes, and here they are.”

For a while, they seemed self-evident. I joined a church. I volunteered with the Red Cross. I left work at work. My ego (as much as it could) went on sabbatical. I ran a half-marathon. I really did feel that in some ways I had reinvented myself. That the perspective I’d lacked has somehow been handed to me free of charge.

Only, it didn’t last. When my cancer came back in 2018, I was pissed. My privilege outweighing my humility (to be fair here, that’s always been a pretty low bar to clear). The steroids I loved the first go-round instead made me moody. I lost my composure over stupid things. I went off in the dugout at a Little League game because the 9-year-old left fielder had the gall to be — a 9-year-old left fielder by placing his glove atop his head while the ball was in play.

Sure, I went back into treatment with the “let’s go” attitude. Sure, I took selfies of me in the chair. Sure you mashed “like” on my Facebook page. I mean, what kind of person doesn’t “like” someone when they say “hey, here’s me fighting cancer.” Yes, I took notes if you didn’t. Yes, I’m keeping score. No, I’m not just kidding.

I gained 25 pounds. I shrugged my shoulders. When my oncologist told me my remission would be shorter this time, I went “meh.” Who cares? Like most movie sequels, the impact of Part II paled in comparison to the urgency of the original. Unlike the first time, I didn’t use my break from treatment as a chance to embrace the things I’d long ignored.

I kept going to church. I didn’t read much of the Bible. Yes, I sang in the choir. No, I didn’t dwell on the meaning of what I was singing (most of the time.) I stopped volunteering for the Red Cross. I stopped running. All the things I’d rightfully minimized resurfaced.

I went back to being the same old “me.” And yeah, that dude is kind of an ass.

The early stages of the pandemic, however briefly, reminded me of those early days of my diagnosis. For a while it was just our family tucked into this protective bubble. We were around each other 24/7. We didn’t drive each other crazy. Our kids didn’t become brats. We got to projects we’d long put off. Even as the world around us went to hell, in some ways I’d never been happier.

The world, however, has this insane habit where it just keeps spinning. It’s relentless like that. And as we’ve started to get back to some semblance of “normal” I found myself falling into habits I’ve long tried to kick. I ran my mouth on Twitter. I attempted to mic drop people in Facebook groups in my constant pursuit to — as comedian John Mulaney put it — become the Mayor of Nothing.

I wrote a long time ago that I expected cancer to shift the tectonic plates within me. I’m still waiting.

That’s why when I saw my numbers start to slide last fall I got … excited? Yeah, kind of excited.

“Woot,” I thought. “I’ll be ‘interesting/sympathetic/hero’ again.”

I girded myself for another round of long days in the treatment chairs, chatting with the nurses. Walking around the other patients — most of whom far sicker than I am — with a “look, I can do this, you can too” air of confidence. The kind that comes not because I am some sort of beacon of anything but because well, I just happened to catch another break in a never-ending string of them.

And in a way, I needed that treatment. A little bit of pain. A little bit of anxiety. A little bit of a brush (a very, very faint brush) with my own mortality.

I viewed it as my penance for those who aren’t as fortunate. For the younger sister of a colleague who died at 20 last year from COVID. For people like my friend Beth, diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer in her late 30s. She’s chronicled her journey in painstaking detail over the last six months. Chemo. (Real chemo, not chemo-lite like I’ve received). Surgery. Radiation. Baldness. Weight loss. All of it.

We have exchanged notes of encouragement over Instagram. I am in awe of her realness. And in a way, when my remission officially ended in early January, I almost looked at going into treatment as a stroke of good fortune. Like, ‘Hell, yeah! I’ve got cancer too baby. I can keep it real too. Let’s Gooooooo.”

Now, I don’t even have that.

Instead of the drip, instead of steroids, instead of rashes and the tremors and the fevers I’m … taking a pill. That’s it. I’m taking a freaking pill.

What a letdown. Where’s the heroism in popping something into your mouth twice a day that — much like parents when the clock ticks past midnight during a sleepover — tells the gene that screws up your bone marrow to shut the hell up and go to sleep?

The plan to go to the pill was semi-last minute. We had planned on real chemo. At my oncologist’s suggestion I went for a second opinion. The doctor I saw suggested the pill, mostly because it’s less toxic and in theory would make me a candidate for a stem cell harvest/transplant down the road, yet another form of therapy that is (checks notes) yes, not nearly as “look at me” as going bald or having surgery or puking my guts out.

The overwhelming feeling I had last night when I took the first one wasn’t anxiety but guilt and some form of Fear Of Missing Out. Why did Beth, who did nothing wrong, get big scary Varsity “holy hell this could kill you” cancer while I got this thing that never really goes away but is now mostly an inconvenience and an “oh by the way” thing?

Maybe I’ll get lucky. The twice-daily pill is not a cure. But it’s going to work for a while. Maybe a long while. But there are also side effects. Most of them run of the mill.

Who knows? Maybe I’ll grow a shell on my back. That’d make me interesting, right?

Meaning … I’m going to be fine. How boring is that?

I have to find a way to define myself. Apparently, cancer isn’t going to sand off the rough edges for me. I’ve tried to let that happen for the last 2500 days or so. I’m still waiting. I’m still struggling to find out why I’ve been spared. I’m terrified that if you strip it away I don’t become some sort of walking story of redemption but just … a pretty damn privileged middle-aged white guy who doesn’t really know what struggle looks like.

I fear there’s a karmic bill coming due that I won’t be able to pay. That the prayers and cards and thoughts that people have sent my way yet again over the last few weeks are being wasted because I am not worthy of them. That I don’t need prayer but some sort of instruction manual titled “OK, Looks Like You’re Going to Live, Here’s What You Do Now Idiot.”

It’s all in my head. God gives grace freely. It’s his greatest gift.

If we had to earn it, we never would. So better just accept it and make the best of it.

I am still an egomaniac. I am still chasing the likes. I am still sometimes far consumed with what others think of me. I’m still a narcissist. (I mean, if you’re still here, I’ve just written 1500 words on it).

But as Jules said at the end of Pulp Fiction.

“I’m trying Ringo. I’m trying real hard.”

For now, that’s going to have to be enough.